“He was very like the chap that I had seen the night before” [STOC]

In the beginning of the nineteenth century, with the rise in literacy and more cost-effective printing and distribution, serialize novels in magazines and newspapers were popular. It’s why the novels of those times were so long; they were first serialized by authors who were being paid by the word. Alexandre Dumas wrote 1.25 million words about the Three Musketeers between 1844 and 1850.

With the acceptance of “A Scandal in Bohemia” in March 1891, Doyle wrote six Holmes stories for The Strand, being paid by the word, averaging £35 for each. When the July, August and September issues hit newsstands, sales increased because of the amateur detective and his medical companion and the magazine asked for more. Doyle offered The Strand £50 per story, regardless of length, hoping the magazine would decline such a ridiculous offer. They did not.

Doyle planned to kill Holmes in the twelfth tale. After informing his mother of that plan, she begged him not to do it and even supplied Doyle with the kernel for the plot of "The Adventure of the Copper Beeches." When The Strand again asked for another Holmes series, Doyle countered with £1000 (approximately $75,000 in US dollars today [Editor's note: calculated by using Currency.Wiki and Dave Manuel's Inflation Calculator) for twelve, again hoping the asking price was too rich for the magazine. It was not and the author stuck to his guns and killed off the detective in the twenty-forth story, “The Final Problem”.

Doyle planned to kill Holmes in the twelfth tale. After informing his mother of that plan, she begged him not to do it and even supplied Doyle with the kernel for the plot of "The Adventure of the Copper Beeches." When The Strand again asked for another Holmes series, Doyle countered with £1000 (approximately $75,000 in US dollars today [Editor's note: calculated by using Currency.Wiki and Dave Manuel's Inflation Calculator) for twelve, again hoping the asking price was too rich for the magazine. It was not and the author stuck to his guns and killed off the detective in the twenty-forth story, “The Final Problem”.

For nine years, “Final” was the operative word when it came to Holmes, but with the worldwide success of William Gillette’s play Sherlock Holmes and mounting personal expenses, Doyle decided to turn his “creeper” of a ghost story into a reminiscence of the late detective and HOUN was the first bestseller of the twentieth century in the modern sense of the term. Such a chink in Doyle’s armor led Collier’s Weekly to offer $25,000 ($715,000 today) for six, $30,000 ($860,000 today) for eight or $45,000 ($1.3 million today) for 13 revived Sherlock Holmes stories, with the Strand throwing in an extra £100 per thousand words. Being human, Doyle accepted.

But also, being Doyle, he went at the task with the highest professional resolve. “I don’t think you need have any fears about Sherlock. I am not conscious of any failing powers, and my work is not less conscientious of old,” Doyle wrote his mother. Watson made clear throughout The Return that Holmes had retired and this was to be the final series of adventures.

But also, being Doyle, he went at the task with the highest professional resolve. “I don’t think you need have any fears about Sherlock. I am not conscious of any failing powers, and my work is not less conscientious of old,” Doyle wrote his mother. Watson made clear throughout The Return that Holmes had retired and this was to be the final series of adventures.

The siren call of cash has power over mortals — and in the nineteen years between 1908 and 1927, Doyle would come to terms with his once-hated nemesis and sporadically write 20 more short stories and one novel. The point is not to berate Doyle for a moral weakness, since what he did was to be well-compensated for giving the public more of what they wanted and not rob or kill for filthy lucre, but to point out that the Canon is a series of stops — and in the fifteen years between Mycroft’s two guest-starring turns, Holmes’s brother had evolved in Doyle’s mind and that the character in "The Greek Interpreter" is subtly different than the one in "The Adventure of the Bruce-Partington Plans"

It is this difference that Robert Doherty and the writers of Elementary exploited in their Mycroft and Morland Holmes.

It is this difference that Robert Doherty and the writers of Elementary exploited in their Mycroft and Morland Holmes.

Interpreting "The Greek Interpreter"

Holmes informing Watson of the existence of a heretofore unknown brother is one of the Canon’s classic scenes; the older sibling with “better powers of observation than I,” but with “no ambition and no energy,” who

Holmes describes the Diogenes:

“audits the books in some of the Government departments. Mycroft lodges in Pall Mall, and he walks round the corner into Whitehall every morning and back every evening. From year's end to year's end he takes no other exercise, and is seen nowhere else, except only in the Diogenes Club, which is just opposite his rooms.”

Holmes describes the Diogenes:

“There are many men in London, you know, who, some from shyness, some from misanthropy, have no wish for the company of their fellows. Yet they are not averse to comfortable chairs and the latest periodicals. It is for the convenience of these that the Diogenes Club was started, and it now contains the most unsociable and unclubbable men in town. No member is permitted to take the least notice of any other one. Save in the Strangers' Room, no talking is, under any circumstances, permitted, and three offences, if brought to the notice of the committee, render the talker liable to expulsion. My brother was one of the founders, and I have myself found it a very soothing atmosphere."

“His body was absolutely corpulent,” Watson describes him on first meeting,

In competing deductions of a stranger on the street we get a hint of sibling rivalry that later pasticheurs and scriptwriters have made much hay over.

“but his face, though massive, had preserved something of the sharpness of expression which was so remarkable in that of his brother. His eyes, which were of a peculiarly light watery grey, seemed to always retain that far-away, introspective look which I had only observed in Sherlock's when he was exerting his full powers.”

|

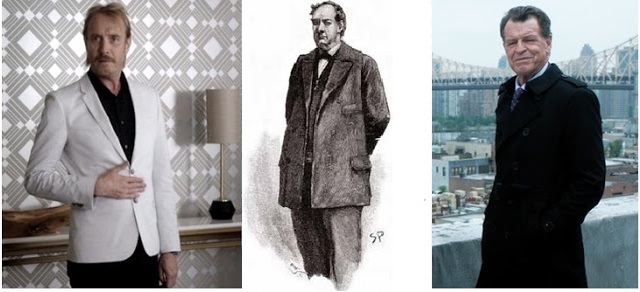

| Mycroft Holmes in "The Greek Interpreter" - illustration by Sidney Paget |

In competing deductions of a stranger on the street we get a hint of sibling rivalry that later pasticheurs and scriptwriters have made much hay over.

Holmes, Watson and Mycroft (for the second time) listen to Mr. Melas’ story then Holmes queries Mycroft on any action he has taken:

“Any steps?” he asked.

Mycroft picked up the Daily News, which was lying on a side-table.

'"Anybody supplying any information as to the whereabouts of a Greek gentleman named Paul Kratides, from Athens, who is unable to speak English, will be rewarded. A similar reward paid to anyone giving information about a Greek lady whose first name is Sophy. X2473.’ That was in all the dailies. No answer.”

“How about the Greek Legation?”

“I have inquired. They know nothing.”

“A wire to the head of the Athens police, then.”'

“Sherlock has all the energy of the family,” said Mycroft, turning to me. “Well, you take up the case by all means, and let me know if you do any good.”

Here is a man to whom writing out two telegraph forms and dispatching a servant to send them puts him on the brink of exhaustion; writing three would send him over the brink. In fact, this picture of an inert and ambitionless man is reinforced when Holmes and Watson walk home from the interview.

Holmes ascended the stairs first, and as he opened the door of our room he gave a start of surprise. Looking over his shoulder I was equally astonished. His brother Mycroft was sitting smoking in the armchair.

"Come in, Sherlock! Come in, sir," said he, blandly, smiling at our surprised faces. "You don't expect such energy from me, do you, Sherlock? But somehow this case attracts me."

[Holmes is so shocked by this unprecedented event that he elicits history’s first instance of “No s—t, Sherlock” from the reader.]"How did you get here?"

"I passed you in a hansom."

If the Canon had ended with the stories of The Memoirs or of The Return, this is the only portrait of Mycroft we would be left with: a lazy and unambitious man, perhaps agoraphobic (“From year's end to year's end he takes no other exercise, and is seen nowhere” except work, home and club) and perhaps misanthropic. An intelligent underachiever content to bookkeep in obscurity and live more within the confines of his mind (“His eyes … seemed to always retain that far-away, introspective look which I had only observed in Sherlock's when he was exerting his full powers”) than the world and behind the façade of a “social club” of fellow hermits.

It is only the intellectual excitement of Sherlock’s work that pulls Mycroft from his comfort zone, and yet for all his intellect makes the tyro error of advertising in the papers after Melas has related the dire consequences of doing just that from Latimer and Kemp and then to suggest to interview the ad respondent rather than to rush to the probable location of the kidnapped Melas and Kratides. As we will see, Elementary’s Mycroft (Rhys Ifans) will draw heavily from this well.

It is only the intellectual excitement of Sherlock’s work that pulls Mycroft from his comfort zone, and yet for all his intellect makes the tyro error of advertising in the papers after Melas has related the dire consequences of doing just that from Latimer and Kemp and then to suggest to interview the ad respondent rather than to rush to the probable location of the kidnapped Melas and Kratides. As we will see, Elementary’s Mycroft (Rhys Ifans) will draw heavily from this well.

Planning "The Bruce-Partington Plans"

Over the fifteen years from GREE to BRUC, Mycroft must have evolved in Doyle’s mind, grown in stature, ability and status from the eccentric recluse to someone more fitting to be the older brother of the world’s first—and best—consulting detective.

Gone is the man with no energy and no ambition. He is not too lazy to go anywhere save work, club and home, but “Mycroft has his rails and he runs on them. His Pall Mall lodgings, the Diogenes Club, Whitehall - that is his cycle. Once, and only once, he has been here. What upheaval can possibly have derailed him?" And “that Mycroft should break out in this erratic fashion! A planet might as well leave its orbit.”

Why? Not because he’s an insignificant accountant too sluggish to move, but because he is a governmental entity too important to be derailed by the trivial.

Why? Not because he’s an insignificant accountant too sluggish to move, but because he is a governmental entity too important to be derailed by the trivial.

"You told me that he had some small office under the British Government."

Holmes chuckled.

"I did not know you quite so well in those days. One has to be discreet when one talks of high matters of state. You are right in thinking that he is under the British Government. You would also be right in a sense if you said that occasionally he is the British Government."

"My dear Holmes!"

"I thought I might surprise you. Mycroft draws four hundred and fifty pounds a year, remains a subordinate, has no ambitions of any kind, will receive neither honour nor title, but remains the most indispensable man in the country."

"But how?"

"Well, his position is unique. He has made it for himself. There has never been anything like it before, nor will be again. He has the tidiest and most orderly brain, with the greatest capacity for storing facts, of any man living. The same great powers which I have turned to the detection of crime he has used for this particular business. The conclusions of every department are passed to him, and he is the central exchange, the clearing-house, which makes out the balance. All other men are specialists, but his specialism is omniscience. We will suppose that a Minister needs information as to a point which involves the Navy, India, Canada, and the bimetallic question; he could get his separate advices from various departments upon each, but only Mycroft can focus them all, and say offhand how each factor would affect the other. They began by using him as a short-cut, a convenience; now he has made himself an essential. In that great brain of his everything is pigeonholed, and can be handed out in an instant. Again and again his word has decided the national policy. He lives in it. He thinks of nothing else save when, as an intellectual exercise, he unbends if I call upon him and ask him to advise me on one of my little problems. But Jupiter is descending today.” [Emphasis ours - Ed.]

Mycroft Holmes is, in fact Her Majesty’s analog to Sherlock Holmes, a consulting intelligence analyst but as superior to the average analyst as Sherlock is to the average Scotland Yarder. He is a department of one, subordinate but independent and like the ship of State itself can only move off-course (or depart Olympus) with great effort and reason. Gone is the lack of energy; the energy is now mental rather than physical. Gone is the lack of ambition for he has created his own, important niche in a realm where only the strong survive; but rather he lacks ambitions — the desire for fame, power or wealth.

Doyle’s physical description of Mycroft is also subtly different.

A moment later the tall and portly form of Mycroft Holmes was ushered into the room. Heavily built and massive, there was a suggestion of uncouth physical inertia in the figure, but above this unwieldy frame there was perched a head so masterful in its brow, so alert in its steel-gray, deep-set eyes, so firm in its lips, and so subtle in its play of expression, that after the first glance one forgot the gross body and remembered only the dominant mind.

The eyes are now alert and steel-gray not introspective and watery gray; the brow so masterful that the seal flipper hand fades from memory. Mycroft has habits, not indolence: “I extremely dislike altering my habits, but the powers that be would take no denial.” Supplicants must come to him prepared: “Give me your details, and from an arm-chair I will return you an excellent expert opinion. But to run here and run there, to cross-question railway guards, and lie on my face with a lens to my eye - it is not my métier.” Doyle paints for us a man worthy of the name Holmes in "The Bruce-Partington Plans" — and that is the one the reader of the Canon remembers the most.

|

| Mycroft Holmes in "The Bruce-Partington Plans" - illustration by Arthur Twidle |

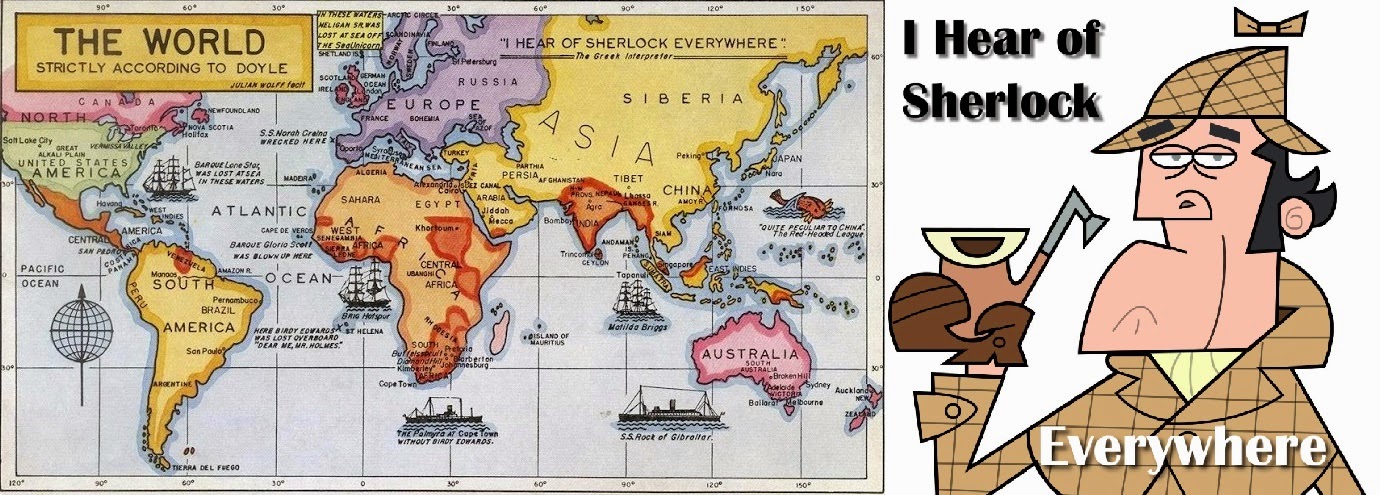

Doyle explains this different Mycroft to the reader by having Holmes claim he did not know Watson well enough to let him in on the truth, one unsatisfying within the confines of The Game, as "The Greek Interpreter" would have to take place after the publication of A Study in Scarlet ("I hear of Sherlock everywhere since you became his chronicler.”). That would place GREE in 1888 at the earliest, which would mean that Holmes did not know Watson well after seven years.

Remember also that in 1883 Holmes contradictorily told Helen Stoner, “This is my intimate friend and associate, Dr. Watson, before whom you can speak as freely as before myself.” A more likely explanation within The Game is that Watson did know truth in 1888, but it was the public who could not know of Mycroft’s position in the government until 1908, when Mycroft’s role was either generally known or he had retired.

While Doyle elevated Mycroft to Sherlock’s governmental analog equal, it was Sherlockians who made Mycroft something more. By taking “he is the British Government” out of the context of Mycroft’s recommendations occasionally being implemented as government policy, Mycroft has become an éminence grise who has the ear of Queen and ministers and powers over purse-strings (as in Billy Wilder’s The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes) or a James Bondian “M” of a proto-MI6 run under the cover of the Diogenes Club or, as Vincent Starrett might have it, a mole of Moriarty. It is this Parallel Mycroft, as Mattias Boström would style it, that Elementary uses as the template for Morland Holmes.

“Morland is not from [the] Canon,” said Robert Doherty at WonderCon 2016, “and in some respects that makes him harder to write. You know if you’re taking something from [the] Canon you’re on some pretty solid footing, but with Morland, he was from whole cloth.” Yes, Holmes père is never mentioned or hinted at in the Canon, but by exploiting the duality of Doyle’s two Mycrofts and the duality of Canonical and popular culture Mycroft, Elementary has created a family dynamic that is influenced by Doyle and the cultural mythos that has built up around Mycroft but is outside the Canon, one both familiar and unique to Sherlockians, exploring how Sherlock became the show’s version of the icon and how the show’s Mycroft became GREE’s underachiever, by having the father be the pop culture Mycroft puppetmaster.

Rhys's Piece

Rhys Ifans’ Mycroft was introduced in Season 2, where it is clear he and brother Sherlock (Jonny Lee Miller) aren't on good terms:Sherlock Holmes: Fatty, This is Watson. Watson, this is Fatty.

Mycroft Holmes: Fatty? I’d say I slimmed down quite a bit. Wouldn’t you say?

Sherlock: Lap-band?

Mycroft: Exercise.

Sherlock: Exercise requires energy and ambition. You’ve never had either. (S2 E1)

This Mycroft is a successful restaurateur who owns several Michelin-starred restaurants named Diogenes. Elementary combines the elements of obesity, work and club [GREE] to give us a Mycroft whose safety zone is food and a self-created environment where he can sate his inner demons. Later in the season we find out that Mycroft was recruited by MI6:

Mycroft Holmes: It’s true, my business was going through a rough patch. I needed cash to keep my restaurants afloat.

Sherlock Holmes: So you took money from drug dealers. What could go wrong?

Mycroft: Le Milieu approached me with what they called a ‘mutually beneficial arraignment’. It was not an offer one could decline and yet that’s precisely what I intended to do. But before I could give my official word, I was visited by a man from MI6. He told me they’d been watching Le Milieu and were aware of the offer; he urged me to accept. Burrow in, keep my eyes and ears open, do some good for Queen and country.

Sherlock: And here was me thinking that MI6 was an intelligence organization. But they sought help from you, a virtual cartoon character.

Mycroft: You’re not listening…. I suppose, at first, it was all very romantic. I was an asset. I was imbedded with Le Milieu. As it turned out, I had something of a knack for spying.

Sherlock: What’s your double-o designation? License to kill or just to annoy?

Mycroft: I never was an operative. Never went on missions. But I did find I had a capacity for storing facts. Quite a remarkable one. And as my work with Le Milieu brought me into contact with other criminal organizations, I began to take on their secrets, too. I became a sort of clearinghouse for MI6. I could often, but not always, predict the effect of certain actions that might be taken to dismantle criminal groups. I know you don’t take me seriously, but the agency does. And they have done for quite some time.

Sherlock: So you honestly expect me to believe that you are an MI6 asset and you have kept that hidden from me for over a decade?

Mycroft: [sarcastically] Right. Because we’re so close. (S2 E23)

As with Melas in "The Greek Interpreter," Mycroft’s action led to a kidnapping — Joan Watson’s (Lucy Liu). Throughout the season, Mycroft had shown a fascination with Sherlock and Joan’s work and during the effort to free Joan from Le Milieu we get a flip version of GREE’s deduction competition:

Sherlock: You have the intellectual tools to make simple deductions. Your failure to apply them in an energetic fashion is a constant source of befuddlement. Look around you. Really look around.

Mycroft: Excuse me. This cushion’s been disturbed. There’s scratches on the floor. Dry blood? There may have been some kind of scuffle.

Sherlock: More than a scuffle, I’d say. Those scratches are drag marks. Someone pulled a heavy object to this door. (S2 E22)

For someone without training, Mycroft acquits himself well, especially, as filmed, the clues are subtle to read. After Joan is rescued, she finds out the depths to which Mycroft would sacrifice for Sherlock. He had quit MI6, to get on with his own life, until:

Joan Watson: Tell me about Sudomo Han ….

Mycroft: Han was an Indonesian businessman who kept an office in London. About three years ago, when Sherlock was at the height of his drug use, or at the bottom, whichever way you look at it, Han approached him to act as a sort of confidential courier. Said he need to transfer a packet of trade secrets to a colleague without his competitors finding out the package had passed hands.

Joan: Sherlock took the job.

Mycroft: Unfortunately. What Sherlock didn’t realize was that Han was financing a terrorist plot. The trade secrets were instructions for the transfer of funds, and the competitors Sherlock managed to elude were British agents. Luckily, MI6 thwarted the attack, so no one was hurt, but in the process Sherlock’s involvement came to light. He, uh…could’ve been sent to prison for a very long time.Joan: So MI6 offered you a deal.

Mycroft: By my handler. He said if I came back to work, Sherlock’s problems would disappear.

Joan: In other words, everything that you did for MI6, letting drug traffickers use your restaurants, that wasn’t for money, or to save your business. That was all to protect Sherlock. (S2 E23)

Mycroft comes to a harsh judgment of his actions and himself:

Mycroft: ‘He has no ambition and no energy. He will not even go out of his way to verify his own solutions. He would rather be considered wrong than go to the trouble of proving himself right.’ Something I overheard Sherlock say to my father once. He was 15.

Joan: I can’t even picture him at 15.

Mycroft: It hurts. And to be assessed like that.

Joan: He knows a lot. He doesn’t know everything.

Mycroft: I could have followed father into business. I could have followed Sherlock into his passions. But I wanted… less, I suppose.

Joan: You are a success. You own restaurants all over Europe. And the things you’ve done for your country---

Mycroft: Folly. Obviously. I should have said no when the agency approached me. But I remembered what Sherlock said. And I remember my father failing to disagree. And I…I thought I could prove, at least to myself, that I was more than what they thought. Idiocy. (S2 E24)

In his own variation of "The Final Problem," Mycroft lets the NSA fake his death to fool Le Milieu and disappears on his own hiatus.

Elementary takes Mycroft's obesity, his desire for obscurity ("How comes it that he is unknown?" "Oh, he is very well known in his own circle." "Where, then?" "Well, in the Diogenes Club, for example." I had never heard of the institution…"), and need for a comfort zone and recombines them.

Food, a symbolic substitute for Mycroft, becomes both his work and his social club. The Diogenes restaurants become the place where he shares that most accessible part of himself with a select clientele. His ambitions are small compared to his father’s and to his brother’s, but like GREE Mycroft's unremarkable bookkeeping job within walking distance of home and unsociable social club, he is happy and content in his self-made world.

Food, a symbolic substitute for Mycroft, becomes both his work and his social club. The Diogenes restaurants become the place where he shares that most accessible part of himself with a select clientele. His ambitions are small compared to his father’s and to his brother’s, but like GREE Mycroft's unremarkable bookkeeping job within walking distance of home and unsociable social club, he is happy and content in his self-made world.

The twist during the course of Season 2 is the blending of this Mycroft with the Canonical Mycroft's government servant and espionage [BRUC]. He is an asset to MI-6, letting his restaurants be used by Le Milieu and being a clearing-house of intel and a strategic analyst. Unlike with Doyle’s Mycroft, the later version does not become the default Mycroft, but Ifans' Greek Interpreter-based Mycroft stays dominant and becomes an uneasy fit to a man trying to prove to himself that he is not the failure his father and brother believe he is. In fact, he did quit only to be lured back in by his handler to prevent Sherlock’s arrest.

Ultimately for some, Elementary’s Mycroft, while hewing close to Doyle, seemed too foreign. They were expecting something more like Parallel or pop culture Mycroft. Indeed, the portrait of Elementary’s Mycroft was incomplete until John Noble appeared to flesh out the family tree and to give the viewers a pastiche theory of how Sherlock and Mycroft Holmes came to be the men they are; “how far any singular gift in an individual was due to his ancestry, and how far to his own early training.”

The Not-So-Noble Father

Father Holmes has been an unseen presence since the beginning of the series. The brownstone occupied by Sherlock and Joan is his least-valuable holding in New York City. Sherlock’s low opinion of bankers, lawyers and capitalists expressed throughout the series has been colored by the relationship with his father: “My father is a Lovecraftian horror who uses his money to bludgeon his way to ever-more-obscene profits.” (S2 E22) Early in the first season, the viewer is teased by the possibility of meeting the man:

Joan Watson: Your father e-mailed me last night before I went to bed. He’s coming into town for business. Wants to have dinner. [Sherlock chuckles] What’s so funny?

Sherlock Holmes: Him. Dinner. Us. [Looks at Joan] You. Remind me, Watson. How many times have you met the man?

Joan: Never.

Sherlock: That’s because he’s secured your services as my sober companion electronically. And all of your subsequent correspondences have been via e-mail or through one of his legion of personal assistants.

Joan: So?

Sherlock: So take it from someone who has spent incrementally more time with him than you, he has zero intentions of meeting us for dinner this evening. (S1 E6)

And later:

Sherlock: One, my father does not care about me. He does what he does out of a sense of familial obligation. Big difference. Two, he does not care about you or what you think. Meeting you would be a formality. Three, as I’ve already told you, your concern is unwarranted because he has absolutely no intention of showing up tonight.

Joan: How could you possible know that?

Sherlock: Because he is a serial absentee. A pathological maker and breaker of promises. Been that way since I was a boy. Fool me one, shame on you, fool me ad nauseam---(S1 E6)

That incrementally and serial absentee are telling. Morland is always away on business; Sherlock and Mycroft were sent to different boarding schools and their mother was an opioid addict who became estranged from Morland and the family, later dying in an apartment fire. While the Canonical Watson thought Holmes was an orphan until "The Greek Interpreter," Elementary’s Sherlock was functionally an orphan.

In Season 4, in a scene that plays like a version of the one in BRUC, Sherlock clarifies his father’s position in the world and the ease in which he can make the improbable happen:

Joan Watson: Look, I think it’s nice that he wants to help, but you know we can’t go back to the department---it’s not possible.

Sherlock Holmes: Neither was war in the Falklands, but the old man tends to get what he wants.

Joan: I can’t tell if you’re serious right now.

Sherlock: How much do you really know about my father? You’ve rarely broached the terms of your initial appointment.

Joan: Mostly I dealt with people under him. I know he’s some sort of international consultant.

Sherlock: It is true I am not the first consultant in the family but the title is where the similarities end. Father’s business exists to grease the skids so that politicians and corporations can operate around the globe. Sometimes these are noble ventures, more times they are not. But they happen because Father is an influence peddler par excellence. If he says he can restore us he means it.

However, Sherlock warns, “With him there is always a cost. The toll always comes due.” (S4 E2) And the Machiavellian nature of Morland comes clearer as the season continues:

Sherlock Holmes: Were you under the impression that we were dealing with a nice man? … Perhaps I underplayed the danger. Perhaps my constantly referring to my father as the devil incarnate wasn’t clear. He has armies on his payroll. He has mercenaries on speed dial. There are countries that you knew the name of as a child that no longer exist because of him. (S4 E22)

This portrait of an amoral power-broker will be familiar to viewers of The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes and Sherlock. While the Parallel Mycroft is the British Government and a master behind-the-scenes manipulator occasionally at odds with his brother, making Morland Holmes his independent business equivalent paints a complex family portrait, combining Canonical and Parallel-Canonical elements, familiar to the Sherlock Holmes fan, but connected in original ways.

Elementary’s Mycroft, unsatisfying to some, becomes more complete when viewed against Morland. Sherlock saw Mycroft cashing in his trust fund as soon as possible to open up Diogenes as lazy and unambitious, but set against a harshly demanding absent but famously successful father and a competitive younger brother...

To open a restaurant, have it not only survive but thrive, to be Michelin-starred, and to open others across Europe is not the calling of a lazy, unambitious buffoon.

Even the addition of elements of "The Bruce-Partington Plans" to Ifans’ Mycroft achieves a deeper meaning. Perhaps Mycroft’s success with Diogenes came relatively easy to him, so he undervalued his efforts and saw himself through his father’s disdain. When MI6 came calling, he saw an opportunity to prove to his father and himself he could be more than a mere restaurateur.

The head of MI6, Sir James Valentine, confirms Mycroft’s worth to the agency. Assessed dispassionately, Mycroft performed much better than Sherlock’s harsh appraisal at the end of Season 2 before departure on hiatus and his heartfelt hug and genuine sentiment “This last year has been a gift,” not only went steps to answering his query to Joan at the beginning of the season of how one becomes Sherlock Holmes’s friend but, as the look on Sherlock’s face confirms after Mycroft leaves, one-ups the detective in their sibling rivalry.

Morland’s complex relationship with Sherlock is wonderfully conveyed John Noble in voice and expression:

Morland is clearly hurt. Speaking of hurt, Joan notices during her lunch meetings with Morland unusual dining habits and numbers and type of vitamins he’s taking and posits that he’s had chemotherapy treatments. While going over Morland’s internet appearances to see if she can detect signs of illness, she comes across the info that Sabine Raoult, a woman Morland was seeing, was killed in a drive-by shooting. Sherlock deduces that two of the bullets never found at the shooting scene ended up inside his father. Morland confirms this and admits the other reason he’s in New York is to get revenge on Sabine’s killer.

Sherlock decides to investigate and discovers that Professor Joshua Vikner (Tony Curran), former mentor and father of Jamie Moriarty’s (Natalie Dormer) daughter had taken over the Moriarty organization and tried to assassinate Morland, but killed Sabine instead.

The offer had come as a bit of a shock to Morland as he no doubt saw himself as one of “the good guys” or the hero of his own life story:

Elementary’s Mycroft, unsatisfying to some, becomes more complete when viewed against Morland. Sherlock saw Mycroft cashing in his trust fund as soon as possible to open up Diogenes as lazy and unambitious, but set against a harshly demanding absent but famously successful father and a competitive younger brother...

Sherlock: [to Morland] Well, it happened rather famously on your one and only visit to Baker Street. Or do you not recall excoriating me for not stocking your favorite tea? [S4 E2]Mycroft’s move can be seen as wisely leaving an unhealthy world and creating a personally satisfying one, as "The Greek Interpreter" Mycroft did in setting up all he would need in England within a block or so in the heart of Whitehall.

To open a restaurant, have it not only survive but thrive, to be Michelin-starred, and to open others across Europe is not the calling of a lazy, unambitious buffoon.

Even the addition of elements of "The Bruce-Partington Plans" to Ifans’ Mycroft achieves a deeper meaning. Perhaps Mycroft’s success with Diogenes came relatively easy to him, so he undervalued his efforts and saw himself through his father’s disdain. When MI6 came calling, he saw an opportunity to prove to his father and himself he could be more than a mere restaurateur.

The head of MI6, Sir James Valentine, confirms Mycroft’s worth to the agency. Assessed dispassionately, Mycroft performed much better than Sherlock’s harsh appraisal at the end of Season 2 before departure on hiatus and his heartfelt hug and genuine sentiment “This last year has been a gift,” not only went steps to answering his query to Joan at the beginning of the season of how one becomes Sherlock Holmes’s friend but, as the look on Sherlock’s face confirms after Mycroft leaves, one-ups the detective in their sibling rivalry.

Morland’s complex relationship with Sherlock is wonderfully conveyed John Noble in voice and expression:

Morland Holmes: When you had your troubles in London, I lost faith in you. I provide for you in New York because I wanted you out of sight and mind. Little did I know that the untended corner of the garden would grow so strong and healthy…. I’m not talking about the last few days, I’m talking about the last few years. I respect what you’ve built here, the work you’ve done. I’m proud of you. Didn’t think I would be. (S4 E2)

The anger, disgust and pride are all there. Morland sees their relationships as worthy opponents on par with a wily business competitor. Joan, in their first face-to-face meeting dissuades him of that notion:

Morland: If you think Sherlock is the only one who considers me an enemy, you’d be wrong.

Joan: He doesn’t consider you an enemy.

Morland: An antagonist, then.

Joan: [matter-of-factly] No. I think he just…thinks you’re a terrible father. (S4 E2)

Morland is clearly hurt. Speaking of hurt, Joan notices during her lunch meetings with Morland unusual dining habits and numbers and type of vitamins he’s taking and posits that he’s had chemotherapy treatments. While going over Morland’s internet appearances to see if she can detect signs of illness, she comes across the info that Sabine Raoult, a woman Morland was seeing, was killed in a drive-by shooting. Sherlock deduces that two of the bullets never found at the shooting scene ended up inside his father. Morland confirms this and admits the other reason he’s in New York is to get revenge on Sabine’s killer.

Sherlock decides to investigate and discovers that Professor Joshua Vikner (Tony Curran), former mentor and father of Jamie Moriarty’s (Natalie Dormer) daughter had taken over the Moriarty organization and tried to assassinate Morland, but killed Sabine instead.

Sherlock: [to Morland about Vikner] I’m sure you’ve been painting a portrait of evil in your mind’s eye since Sabine’s death, but it’s really not like that. A closer approximate would be Great Uncle Willard as a younger man.” (S4 E24)

We don’t know if Miller’s Sherlock is related to Vernet, however we can say that “Capitalism is the blood is liable to take the strangest forms.” Morland had assumed that he had angered a rival business competitor, but is puzzled as to why Vikner would try to kill him. Sherlock had deduce that there was dissent in the Moriarty organization over Vikner’s leadership, headed by Iranian diplomat Zoya Hashemi (Roma Chugani). Morland, Sherlock and Joan interview Hashemi and get a sense of how large the criminal organization is; they have a presence, large or small, in about half the countries of the world.

Hashemi: When Moriarty was captured, those with the most influence in the group realized that we couldn’t continue on without a leader. We were, as you said, a snake and we were eating our own tail. Certain candidates emerged---Vikner was one of them. But others, like myself, advocated for an individual outside the group, a man we long admired. A legend. He had spent a lifetime playing dice with the globe and had profited immensely. He still does.

Sherlock: [to Morland] She’s talking about you. They wanted you to lead them.

Hashemi: Tell me you don’t see art in what we do. Tell me you couldn’t have perfected it. (S4 E24)

Morland’s wounding and Sabine’s death accomplished the same result as Morland’s death would have; it gave Vikner enough time to consolidate his leadership over the group. Sherlock asks Hashemi to help “roll up” the group, but she replies it is too big to jail. Later at the brownstone, Joan asks:

Joan: Do you think Morland would have said “yes” to the offer to take over the group?

Sherlock: No. There’s no denying over his long and storied career my father has facilitated deals where death was the likely outcome for someone, somewhere. But Vikner and his people persue death as a business deal. It’s a difference of kind, not of degree.

The offer had come as a bit of a shock to Morland as he no doubt saw himself as one of “the good guys” or the hero of his own life story:

Morland: It’s really something, realizing you are, for all appearances, the kind of man who would accept the leadership position in a group like that. I’ve always blamed myself for what happened to Sabine. I was sure I had done something to upset a competitor or acted too aggressively in a negotiation, angered the wrong dictator or CEO. I’d stay up at night struggling to put a finger on it, to figure out exactly what I had done wrong.

Sherlock: Right. ‘Cause it wasn’t one thing, was it? It was everything. Your life’s work. You would have been a spectacular failure, by the way. You don’t have the stuff to be an evil mastermind.(S4 E24)

Parallel Mycroft works in a moral gray area; the needs of the government outweigh the rights of individuals or the niceties of international laws. In The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, Queen Victoria, coming to the understanding of the unsportsman-like nature of submarine warfare orders Mycroft to destroy his prototype. Mycroft allows the German agents to steal the sub and rigged it to sink after theft---which also seems a bit unsportsman-like. By making Morland a Parallel Mycroft, Elementary shows us, in the context of the Game, how Sherlock became Holmes, the man who would “rather play tricks with the law of England than with my own conscience” [ABBE] while still having a code of ethics, by contrasting him with a father who is not evil but,

Sherlock: Father’s work is anything but frivolous, I assure you. Thanks to him, this energy firm and other clients like them have literally brought light to lands that were dark and just as often rained darkness where once there was light. Father doesn’t distinguish. Perhaps you need sanctions eased against a rogue nation so you can sell them your tanks, or your factories can only spew toxins if the US doesn’t sign an emissions treaty. Father can make it so, with the moral neutrality of the plague…. Not evil. Neutral. Like a shark, or a tsunami. (S4 E3)

The difference between Sherlock’s sense of justice and Morland’s moral relativism is critical, especially as we see throughout Season 4, father and son have similar modus operandi for achieving results, such as threats and bribery. In Sherlock’s case, the threats are exposure of criminal activity or the bribe a quid pro quo to not expose criminal activity in exchange for information to bring a larger crime to justice. Morland uses them as a means to an end.

As the Holmeses work together, Joan, who like the Canonical Watson doesn’t mind breaking the law or facing arrest in service of a good cause, keeps a wary eye on them both to make sure Morland doesn’t corrupt and Sherlock doesn’t become corrupted. He does admit to Joan that he could get used to having a helicopter at his disposal to avoid New York traffic. But as we see, while Sherlock might naturally wish for a rapprochement his father, he has come to reject the moral neutrality that allows Morland—and the Parallel Mycroft of pastiche—of using people, loved ones, corporations and governments as chess pieces to be moved and sacrificed for an end-game. The dominant father-figure of Parallel Mycroft gives the characters of Sherlock and his brother a psychological depth for Canonical traits taken from Doyle and repurposed in both familiar and original configurations in, not a retelling of the Canon, but an exploration of a version of the essence of Sherlock Holmes, Doctor Watson, family and partnership.

The differences between father and son are displayed on the rooftop of the Brownstone at the end of season four when Morland informs Sherlock he has accepted Hashemi’s offer to head the Moriarty group, which resulted in Professor Vikner’s assassination.

Morland: I told you, I will not lose my son.

Sherlock: So your only recourse is to become the head of an organization which murders for profit?

Morland: How else would I dismantle it? Ms. Hashemi was right, the group is virtually impervious to threats from the outside, but a threat from the inside on the other hand…

Sherlock: What you’re describing would be suicide.

Morland: I should be returning to London this evening. The group will no longer have a presence in New York. You have my word. What is it about you and I that we do so much harm to the ones we allege we care about? I know about Irene Adler now. Ms. Hashemi explained. For years, you’ve blamed yourself for her death. You never questioned it … and the case could be made that your brother is in banishment because of you.

Sherlock: Do you have a point?

Morland: Being loved by you is a dangerous thing, Sherlock. Probably why I’m still alive. Men like us… we’re not meant to make such connections.

Sherlock: I disagree.

Morland: Ask yourself: who do love more than any other in the world? And what do you think will happen if you stay with her?

As performed by John Noble, the viewer believes Morland is infiltrating the group to destroy it—to save his son in a gambit where the grand master is willing to sacrifice a bishop (Vikner) and his Queen (himself) to save the King (Sherlock). We believe Miller that he’s come to see Morland as human (“You don’t have the stuff to be an evil mastermind.”), although not forgiven for his paternal failings. He was willing to frame the Professor for a murder committed by one of his hired assassins who already languishes in prison, but Vikner’s murder was out of the question for Sherlock. We know what Morland would do for those he loves; Sherlock, like the Doyle’s Holmes, has “a great heart as well as ... a great brain” [3GAR] and a moral compass. Parallel Mycroft-as-father-figure puts those differences in stark relief.

Stay Tuned

Elementary’s Sherlock is capable of growth and the arc of the series has been to follow the great detective from the nadir of addiction, that dulling of distractions in too-sharp of focus, through the redemption of true friendship with Joan, something that didn’t exist in his familial relationships. Elementary does this not by a retelling of Canonical stories, but by using the Canon, and the pop culture canon, in original ways.

The fourth season of Elementary will be out on DVD August 23, 2016 and the fifth season will premiere on CBS Sunday, October 2, 2016 at 10:00 pm ET.

I do not know what’s in store. I would love to see a story arc showing Morland dismantling the Moriarty organization from the inside, perhaps with Mycroft's help and Jamie Moriarty emerging from the shadows to protect her empire, but the realities of actor availabilities will no doubt triumph over my personal wishes. However, I am looking forward to what Robert Doherty, Bob Goodman, the writing staff and the cast will have for us.

I do not know what’s in store. I would love to see a story arc showing Morland dismantling the Moriarty organization from the inside, perhaps with Mycroft's help and Jamie Moriarty emerging from the shadows to protect her empire, but the realities of actor availabilities will no doubt triumph over my personal wishes. However, I am looking forward to what Robert Doherty, Bob Goodman, the writing staff and the cast will have for us.

Author’s note: My quotes from the TV show are based on the closed captioning and the dialog as I hear it. I’ve done the best I can to be accurate.

--

0 comments:

Post a Comment